Origins of a Voice for Freedom

Born in Twic County during the Anglo-Egyptian era, Bona Malwal Madut Ring entered journalism because it offered a megaphone to suppressed communities. Friends say his conviction that words matter crystallised amid the post-colonial turbulence that engulfed Sudan’s southern provinces.

Early mentors recall a studious youth devouring newspapers at Rumbek Secondary, later reading politics at the University of Khartoum. The seeds of dissent, they note, were sown not in anger but in a lawyerly insistence on constitutional guarantees promised by independence.

Sedition Trial that Shocked Khartoum

On 26 May 1965 the English-language daily Vigilant printed his editorial titled ‘Ours is a National Liberation Movement’. Prosecutors invoked sections 105 and 106 of the 1925 Penal Code, alleging the article incited hatred and illegal opposition against the Sudanese state.

In a packed courtroom led by Judge Dafalla El Radi Siddiq, defence counsel Abel Alier argued free speech was being criminalised. Co-accused Darios Bashir and Chan Malwal were acquitted, yet Bona accepted authorship and received a prison sentence that turned him into a household name.

Academic Exile and Global Advocacy

Released amid shifting political winds, Bona pursued graduate studies in the United States and Britain. Lectures at Columbia and later as a senior research fellow at Oxford’s St Antony’s College widened his network while offering western audiences first-hand testimony of southern grievances.

Contemporaries remember full lecture halls where he calmly compared Sudan’s constitution with universal civil-rights norms, framing secession not as rebellion but as remedial self-determination. Those arguments helped diplomats comprehend why violence had supplanted dialogue by the late 1960s.

A Voice During Darkest Hours

Military crackdowns in Juba on 8 July 1965 and Wau three days later killed hundreds, according to eyewitnesses cited in Vigilant archives. Bona’s editorials condemned the massacres, a stance reviewers say contributed to the harsh tone adopted by appellate judge Abdel Magid Imam.

Yet within southern communities, the trial symbolised resistance rather than defeat. Oral historians recount clandestine readings of the judgment, its legalistic prose fuelling recruitment for the nascent Anyanya movement and fortifying calls for eventual independence declared in 2011.

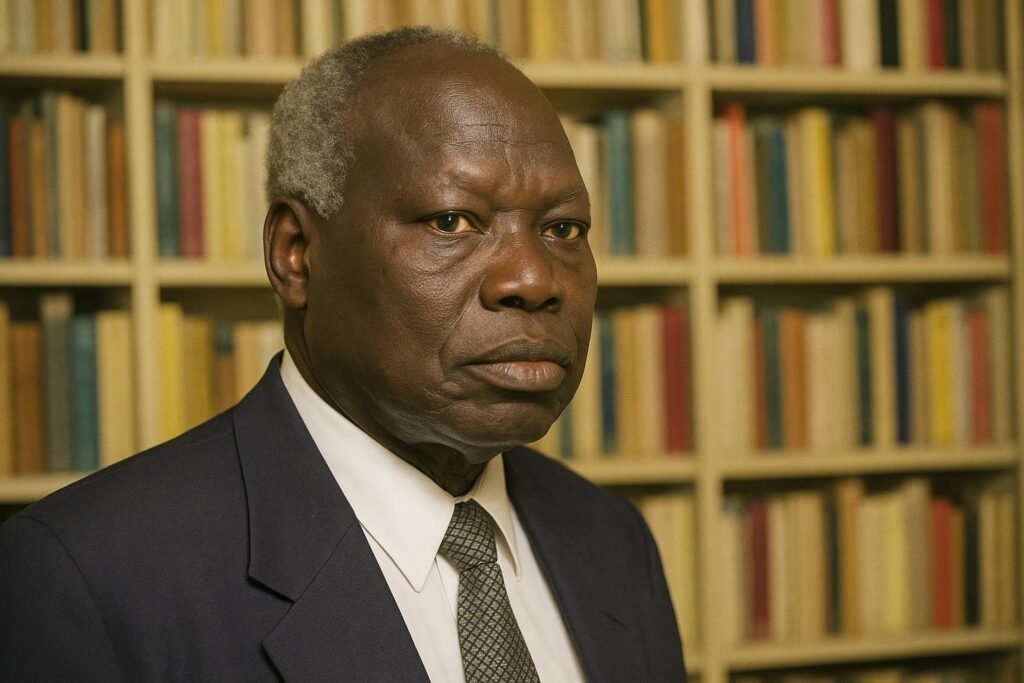

Legacy After 2 November 2025

When Bona Malwal passed at 88, tributes flowed from Juba to Nairobi. President Salva Kiir praised a ‘patriot who never wavered’. Scholars credit him for linking journalism, law and diplomacy in pursuit of rights later enshrined in South Sudan’s constitution.

Legal analysts argue the 1965 decision still offers cautionary lessons: that sedition statutes, if loosely applied, jeopardise national dialogue. Conversely, Bona’s composure illustrates how dissent can inhabit legal channels even under duress, reinforcing civic culture rather than eroding it.

Looking Ahead

South Sudan’s youthful population now debates federalism, oil governance and reconciliation. Remembering Bona Malwal, lecturers urge students to marry principled argument with respectful tone, ensuring grievances reach policy tables without reopening wartime wounds.

Archives of Vigilant are being digitised in Juba, promising open access to primary documents that shaped the liberation narrative. For many readers, the project reaffirms the power of the written word in charting Africa’s political futures.