Survival governance in South Sudan

President Salva Kiir’s style is often described by analysts as governance by fragmentation rather than institution-building. Through selective patronage and calculated mistrust, he maintains authority while preventing any faction from coalescing into an organised opposition.

Parliament, army and bureaucracy remain deliberately weak; none can generate an autonomous leader. External rents—from oil, donors and neighbours—cushion the state, allowing endurance to trump reform even during economic stress.

Elite balancing tactics around Kiir

Business magnate Bol Mel and first daughter Adut Salva illustrate Kiir’s balancing. Bol channels public anger over shortages, protecting the presidency, while Adut reinforces dynastic legitimacy and quietly checks Bol’s rise, ensuring no single figure becomes a rallying point.

Such calibrated rivalry keeps elites dependent on Kiir’s favour. Scholars call it the “instrumentalisation of disorder,” where controlled uncertainty becomes a governing tool rather than a problem to solve.

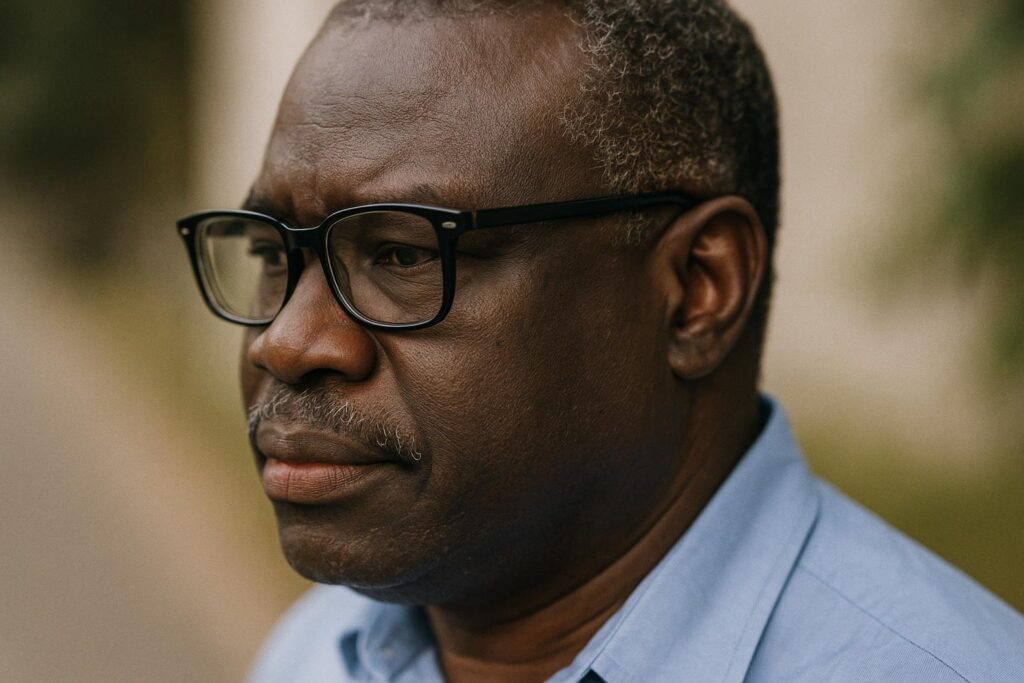

The legal limbo strategy against Machar

The forthcoming criminal case against opposition leader Dr. Riek Machar slots neatly into this playbook. By placing him under permanent judicial shadow, the presidency curbs his capacity to mobilise while avoiding the political costs of outright detention or exile.

Few observers expect a rapid verdict. Adjournments, procedural debates and shifting panels create a legal purgatory in which Machar is neither condemned nor cleared, a visible reminder that alternatives exist only at the head of state’s discretion.

Judiciary’s credibility at stake

South Sudan’s courts, sidelined during past crises and major corruption scandals, now face a defining credibility test. Will they act as a neutral arbiter or be seen as another spoke in the wheel of survival politics?

Legal researcher Atong Kuol warns, “If judges surrender autonomy today, they may never recover society’s trust tomorrow.” Conversely, a steadfast bench could re-ignite hope in constitutional guarantees promised at independence.

Regional lessons on judicial independence

The region offers contrasts. Kenya’s Supreme Court annulled a presidential poll in 2017, while South Africa’s Constitutional Court reined in executive excess under Jacob Zuma. Each case shows that judicial resolve can reset political calculations.

Whether Juba follows those precedents or deepens its pattern of legal theatre now rests with the men and women in black robes. Their choice could shape public faith and elite bargaining for years ahead.